When I started bonsai in 2009 I was taught the art according to Japanese tradition. I studied all the styles and rules and tried to grow my bonsai according to them.

I joined the local bonsai kai and was very sad because I could not exhibit trees. Most of my trees were dug or bought from normal garden nurseries - not ready to show anywhere!

I cheated and bought a "finished" Buxus from a guy that had to move to a smaller place:

This Buxus was 10 years old then and was I very proud! I showed it everywhere, and to feel not so guilty of not styling it myself, I did gave credit to the previous owner.

One day I showed it at the church's fair and a farmer made a remark that he did not like the tree - according to him trees do not look like that!

I was not very happy with the remark - but it made me think for many years!

Growing the pads out a bit, it did look better:

I also studied Charles Ceronio's book, Bonsai styles of the world, and I was impressed by the natural forms/shapes of the African species he described in his book.

When Walter Pall posted a thread on the natural/naturalistic style of trees and also the hedge pruning method on a forum, I became very confused - I was even angry and negative towards the guy!

http://walterpallbonsaiarticles.blogspot.com/2010/09/naturalistic-bonsai-style-english.html

(Very well written article!)

I like his trees very much(The same as I liked my naturalistic styled Acacia), but I also like my Buxus with the traditional styled pads, I also like my Ent tree, my Buddha Ficus, my Ginseng Ficus with the fat roots, my Octopus Brush Cherry, my Buddleja styled into a lightning struck Pine form, my Celtis grown into a Baobab form and also a lot of others not looking like their natural counterparts and the branches not always structured in a very natural way.

...........and after a lot of thinking I decided, that for my self, I can grow a tree in a pot into anything, as long as it is beautiful to me - and I would even appreciate a topiary tree in a pot, as long as it is well done.

But I also realize that people all over the world see bonsai differently - if I want to enter a tree into a competition and the trees are judged according to a set rules for the specific competition, I can not be unhappy if my tree do not do well!

But to understand the naturalistic style/form, because I do want trees looking like natural trees, I came up with the following to clear things up for myself:

1. Natural form of a species determined by genetics.

Species of trees, all over the world, would have very distinctive forms/shapes if they grew in perfect conditions. Their genes will determine how they look.But even being the same species, the shape/form of a species can differ tremendously. Here are recognized forms of Irvingia gabonensis

Here are some general shapes/forms named:

(CREDIT : www.dot.ny.gov/divisions/engineering/design/landscape/trees/rs_selections)

Some real trees in their predetermined shapes:

PINE

DRAGON TREE

YOUNG BAOBAB

MAPLE

Willow

Notice the different forms of the individual species. In general these trees grew into their natural shapes determined by their genetics. And there are thousands of species of trees in the world - in perfect conditions each one will have a determined shape/form.

Nature is indeed wonderful!

In bonsai terms, if you grow a tree into its natural form/shape, you will grow a tree into its genetic predetermined shape where there are no other influences visible. In general this means that you will grow a tree up to the stage before nature and age are starting to change the form/shape of the tree also.

But trees rarely keep/show the shape/form as determined by their genetics. There are many things that will change the shape of a tree:

2. Trees that lost their species genetic shape naturally.

A. AGE: Age can change a tree in may ways.

- Branches may lower under their own weight.- sometimes the lowest branches may even touch the ground.

- Branches may tear from the trunk because of the weight - sometimes a strip of the trunk may be torn off leaving a big scar.

- Bottom branches may die because they are shaded from the crown above.

B. SNOW: Snow flakes are very light but if they heap up on a branch - they become very heavy!

- Snow can cause branches to grow in a downward sweeping movement.

- Snow can break branches and trunks can also be torn by this.

- An avalanche can cause havoc - they can even tear away trees from the soil and strip trees from all branches.

A snow broken Juniper:

( CREDIT ; http://samedge.files.wordpress.com/2010/11/sierra_1251.jpg )

C. WATER(Including melting snow and mud slides): Working at the roots or even uprooting trees!

Floods may expose roots.Floods, with a lot of debris coming down, may break branches and even trunks.

- Floods may expose roots

- Floods may uproot trees.

- Floods, with a lot of debris coming down, may break branches and even trunks.

An American Sycamore:

https://artistatexit0.wordpress.com/tag/tree-roots/

D. WIND- This includes constant light or strong winds, storms, hurricanes, upward and down blowing winds/drafts.

- Light and strong constant blowing winds causes trees to grow to the one side that is in the opposite side of the direction of the wind. Heavy branch breakage is not always visible but may happen.

- Storms may break branches and trunks causing the tree to grow to the one side. Trees may also be uprooted in strong winds. Deadwood is common.

A windblown tree:

(CREDIT: http://cindyknoke.com/2013/02/06/ushuaias-twisted-trees/ )

A probably, storm damaged tree, many years later:

(CREDIT : http://www.oliveoilsource.com/files/trees/Olive_tree_4.jpg )

E. LIGHTNING STRUCK - sometimes they explode, sometimes they survive.

- The result of being hit by lightning is a lot of deadwood - long pieces of the trunk is ripped of and branches may die.

One that has survived:

(CREDIT: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:TreeStruckByLightning.JPG)

F. SHADING/COMPETITION - These two factors my also change the natural form of a tree.

- Trees may slant slight to heavily to grow out of the shade of other trees, rocks or cliffs.

- When trees are growing together with others in groups or forest, they may shed lower branches and grow only a crown that may reach the sunlight.

(CREDIT: http://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/olympia/silv/oak-studies/acorn_survey/survey-background.shtml)

Nice example of a tree growing away from the shaded rock face:

G. OTHER things that may change the natural shape/form of a species:

- Animals may damage the leader or lower branches of a tree:

- Fires may damage trunks and branches- especially branches killing them from below.

- Diseases and insects can also change the natural shape/form of a tree.

Are these trees natural? Yes, they are - nature changed them.

They do not look like natural species "perfect" form/shape anymore, but they are natural.

In bonsai terms, all the above trees are in a natural form/shape - but not natural in the sense of the genetic natural determined form/shape. In a matter of fact, most trees changed by a natural cause, do not look like the original genetic determined shape/form.

This is a relative young Olive in its natural genetic determined shape:

(Credit: http://filesite.org/treepic/olive-tree-9.jpg)

This is a natural Olive where its original shape/form was changed by probably many natural things:

(Credit: http://community.humanityhealing.net )

To not confuse people, it would be best to name our trees correctly:

1. Natural species's form/shape.

2. Natural changed by nature form/shape.

(If a tree is changed by nature it will try and regrow back to the genetic determined shape/form.)

3. And why all the politics about traditional and modern/natural bonsai?

It is all about the structure and placement of the branches and twigs.

There are not many species of trees that will form flat pads on a branch - but they do!

Here is a picture of trees in the Yellow mountains showing this flat pads:

It seems that it is mostly Pine-like trees showing this highly defined pads where the leaves stay alive close to the trunk. It seems that these spaced branches and flat pads allow enough sunlight into the tree for the leaves, in this case needles, to keep on growing.

And these pads can be very thin:

(CREDIT: http://trailofneonfeathers.wordpress.com/2012/11/13/huangshan-the-yellow-mountains/chinese-tree/)

Notice how thin the pads are!

When it comes to bonsai, this branch structure is very natural for the species.

Why are they so flat?

Wind can have an influence here.

Here is an example of a tree grown into this natural, very flat branch structure:

(CREDIT: http://bonsailo.blogspot.com/2013/05/bci-2013-yangzhou-2.html)

But most natural trees do not grow their branches so flat.

Most trees will send out branches/growth wherever their is a sunny spot available. On younger trees where nature did not change the genetic determined shape/form, the crown will have a very neat outline, showing almost no pads:

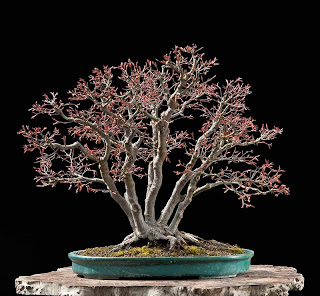

Have a look at this Maple:

There are no pads visible. The outline of this tree is formed by many long thin branches that ramify at the very end of the outline of the crown. Twigs growing deep inside the crown will normally die back because the do not get enough sunlight. The leaves only grow on the outer tips on thin twigs:

But when age and nature steps in, the shape/form and the branch structure change.

On older trees the branches originating directly from the trunk becomes less - this is probably because of the competition for sunlight. On older trees the branches also loose their straightness. The outline of the crown also becomes very irregular, showing branch outlines flowing into each other.

Here is an natural example of an older tree showing the above:

This is how the branch and twig structure may look on an older tree:

When it comes to bonsai, the above is how the branch structure will look if we want to depict a tree in its natural shape/form and with its branches structured in a natural tree's branch structure.

Even when a tree's shape/form is changed by nature, whether by struck by lightning, wind etc. the remaining branches will have to be structured as in the above sketches to be called natural.

Here are a few examples of trees where the branches were styled into the natural structure of natural trees:

(All pictures credit Walter Pall : http://walter-pall.de/00gallery/index.html )

And South Africa has not fallen behind growing trees with the branches structured naturally:

Here is a Celtis grown by Andre Beaurain in its early development:

This tendency to style branches more naturally has taken favor all over the world - just looking at shows in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines etc, show this styling is here to stay.

How is bonsai grown into this natural styling of branches?

Here Walter Pall describes his method:

Refurbishing a Japanese maple - the "hedge cutting method"

Picture 1: 2008-05: The tree arrived in my garden in this state. The previous owner had kept it in Akadama mush and thought that he would automatically improve the tree by pinching. The crown is much too wide and flat and the leaves hide poorly structured branches. Many branches are dead. The Nebari could be much better and the maple is planted too high in its pot.

Picture 2: 2008-05: The much too dense substrate lead to severe damage in the upper parts of the crown. Many small leaved varieties of Acer palmatum are basally dominant which means that the lower branches tend to be strong while the upper branches might be abandoned. This is exactly the opposite of most other trees. The picture likely shows the rear of the tree, although the nebari appears to look better than from the front.

Picture 3: 2008-05: The first step was a strong cut back. The silhouette is deliberately kept a little smaller than ideal to allow room for additional growth. If you were cut back to the ideal shape, then the crown would soon grow too large and would have to be cut back hard again.

Picture 4: 2008-05: I would have loved to free the tree from the compacted Akadama, but it was clearly too late in the year. It would have been possible in the fall, but it wasn’t that critical. In any case, the nebari was worked out strongly. It already was a big improvement. The tree is not positioned well in its pot.

Picture 5: 2008-07: Because this variety is basally dominant, the top has to be strengthened by allowing some selected shoots to grow freely. The center trunk ought to be the biggest and thickest. If it is not worked on actively, the exact opposite happens. Especially this trunk must be strengthened by using sacrifice branches; otherwise it could even die.

Picture 6: 2009-01: A deciduous tree can be much better evaluated without its leaves. It is now apparent that the center tree ought to be much thicker and somewhat higher. The previous owner didn’t achieve much by many years of pinching. It looks rather poorly developed. The pot by Bryan Albright seems over powering.

Picture 7: 2009-04: The maple was repotted into a better pot from Japan. Most of the compacted Akadama was removed. The root ball was heavily reduced and the roots loosened up. For the substrate, many materials are suitable that don’t break down in cold and moisture. In this case I used expanded clay with 15 % rough peat. This allows heavy watering and feeding without having to worry.

Picture 8: 2009-11: The development in two growth periods is already well advanced. The branches are better ramified, the main trunk is stronger, and the nebari is improving constantly. The crown is still a little too flat. Now is the best time for detailed work on the crown.

Picture 9: 2009-11: The sacrifice branches in the crown must not be allowed to become too thick, otherwise they will develop ugly scars. That is why they are removed entirely and regrown in the next summer. The crown is worked on with a pair of pointy sharp scissors. Dead branchlets and branch stumps are removed. The branches are cut back to one or two buds, and those that grow into the wrong direction must be removed completely.

Picture 10: 2010-03: Two years after the restoration, the tree is looking pretty good. Japanese maples are very handsome trees that in each season look different but always lovely. This is especially the case in spring. Despite this, the crown must be developed further - contentment is the end of Art.

Picture 11: 2010-10: The tree looks very good in the fall too. Yet this is not yet the time to exhibit the tree. The trunks must continue to be corrected. With strong guy wires they are forced into new positions. It is advantageous to exaggerate somewhat because the tree will spring back a little anyway.

Picture 12: 2010-11: After the guy wires were removed and the crown was carefully cleaned out, the tree was - for the first time - truly ready for exhibition. Of course, there are still problems. The large wound on the front trunk is ugly to look at at. But there’s nothing to be done except to wait for many years. The middle trunk is now clearly the highest and the crown isn’t entirely flat and even.

Picture 13: 2011-03: It is tempting to see this lovely new growth as a signal that the tree is ‘finished’ and to enjoy its beauty from now on. But that would be a compromise over the long term. The main trunk must continue to grow strongly, the wounds must heal, and the nebari can be improved much. But something like that doesn’t happen on its own - it requires a lot of work.

Picture 14: 2011-04: Here you can clearly see that pinching was completely avoided. The tree was allowed to grow out fully. Six or more weeks later, the new growth has become fairly long. Now, the crown is cut quickly with a hedge pruner. In deed, it is like pruning a hedge. The exact cut is not important, and it even doesn’t matter if leaves are partially cut. Only the long term success counts.

Picture 15: 2011-10: During the summer, the tree was cut twice with the hedge pruners. Selected sacrifice branches were allowed to grow unrestricted. Momentary beauty is sacrificed for long term quality. It will be a few more years like this. This is the only way to turn an average tree into a top bonsai.

Picture 16: 2011-10: In the fall, the tree’s crown is cut again with the hedge pruners, even the sacrifice branches. As long as there a leaves on the branches it doesn’t make much sense to look too closely where and what is being cut. That will happen in a few weeks when the tree is bare. The picture shows real hedge pruners.

Picture 17: 2011-10: The result doesn’t look too bad at all. But the tree was designed for its winter view. As long as the leaves are on the tree, you can’t really see it. The crown is nothing but a big ball of leaves. Amateurs usually prefer that a tree looks good in the summer, but pros prefer the winter image. A compromise isn’t always helpful and usually leads to weaknesses over all.

Picture 18: 2011-11: Four weeks later, the leaves are removed. The crown is now carefully pruned. At this point you can only guess at where the sacrifice branches once grew; the wounds are growing out well. Two of the trunks in the group must still be forced into a better position. Unfortunately this is only possible with ugly guy wires.

Picture 19: 2012-04: This view is reward for all the work. The guy wires are only removed for the pictures, and then reattached afterward. Because the rest is almost perfect, the big ugly wound in the front tree is now very apparent. Although it has healed noticeable since the maple was able to built much energy though it lush growth. The main trunk could also become much stronger yet - but this is whining at a high level.

Picture 20: 2012-12:

It is November and the leaves are removed again. One can clearly see that some

branches are too long and a few ugly branch stumps were left over. The tree is now

cleaned out with a pair of pointy, sharp scissors. In a few years, one should get the feeling

that Mother Nature is the best artist, and that she creates the best crowns. The hand of

man will eventually become invisible, even though he did so much.

Picture 21: 2012-12:

Slowly the tree is turning out as it should. The crown looks balanced and the entire group

looks as if it had gracefully grown on its own. This, perhaps, gives the viewer the idea that

something like this is result of a hands-off approach. The development so far, however,

teaches the opposite: only through strong and very focused interventions over many years

can such a natural shape be developed.

Picture 22: 2013-02: The tree was repotted into a very suitable pot by Walter Venne from Germany. The results of the development thus far are quite presentable. But is is by far not the end of the development. Much has changed in five growth periods, yet the work continues as before. In another five years the tree will be better again. The drawback, however, will be that he tree is not really presentable during much of that time.

Is this a real tree? Or is it a bonsai?

And can a tree, that was styled with very defined pads, be restyled into a more naturalistic styled branches way?

I think they can. Here is a Brush Cherry that was styled with very flat pads:

This tree was one of my very first trees and I tried to style it in the traditional way with flat pads - the idea was to have pads flowing into pads when the tree was finished. I defoliated the tree February 2014 and was again not happy with the tree. I rewired the tree and reset the secondary and tertiary branches with their twigs - I bent some down and some upwards to fill in the open spaces. I could not do drastic bends because the branches are quite brittle.

Here is the tree after I reset the branches:

Slightly from above:

The tree does look better now but it looks sloppy. Over time I will do some more bending an I will also wire the fine twigs to set them in the natural twig structure.

The tree will also be grown I little bit higher(The yellow arrow indicate the new trunkline in the crown.) - at this stage the crown's height and the height of the trunk below the first branch is the same. I want it to look a little bit more like this tree of Walter Pall:

To conclude - anyone wanting to comment on this is welcome, this way we can learn more.

(I tried not to use copy righted pictures - if I did I ask forgiveness. Please contact me if you want me to remove your picture.)