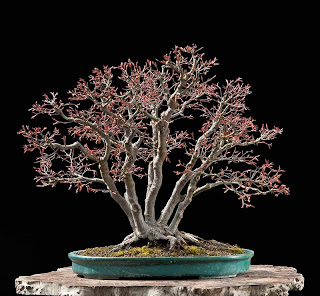

Picture 1: 2008-05:

The tree arrived in my garden in this state. The previous owner had

kept it in Akadama mush and thought that he would automatically improve the tree by

pinching. The crown is much too wide and flat and the leaves hide poorly structured

branches. Many branches are dead. The Nebari could be much better and the maple is

planted too high in its pot.

Picture 2: 2008-05:

The much too dense substrate lead to severe damage in the upper parts of the crown. Many small

leaved varieties of Acer palmatum are basally dominant which means that the lower branches tend

to be strong while the upper branches might be abandoned. This is exactly the opposite of most

other trees. The picture likely shows the rear of the tree, although the nebari appears to look

better than from the front.

Picture 3: 2008-05:

The first step was a strong cut back. The silhouette is deliberately kept a little smaller than

ideal to allow room for additional growth. If you were cut back to the ideal shape, then the

crown would soon grow too large and would have to be cut back hard again.

Picture 4: 2008-05:

I would have loved to free the tree from the compacted Akadama, but it was clearly too late

in the year. It would have been possible in the fall, but it wasn’t that critical. In any case,

the nebari was worked out strongly. It already was a big improvement. The tree is not

positioned well in its pot.

Picture 5: 2008-07:

Because this variety is basally dominant, the top has to be strengthened by allowing some

selected shoots to grow freely. The center trunk ought to be the biggest and thickest. If it is

not worked on actively, the exact opposite happens. Especially this trunk must be

strengthened by using sacrifice branches; otherwise it could even die.

Picture 6: 2009-01:

A deciduous tree can be much better evaluated without its leaves. It is now apparent that

the center tree ought to be much thicker and somewhat higher. The previous owner didn’t

achieve much by many years of pinching. It looks rather poorly developed. The pot by

Bryan Albright seems over powering.

Picture 7: 2009-04:

The maple was repotted into a better pot from Japan. Most of the compacted Akadama

was removed. The root ball was heavily reduced and the roots loosened up. For the

substrate, many materials are suitable that don’t break down in cold and moisture. In this

case I used expanded clay with 15 % rough peat. This allows heavy watering and feeding without

having to worry.

Picture 8: 2009-11:

The development in two growth periods is already well advanced. The branches are better

ramified, the main trunk is stronger, and the nebari is improving constantly. The crown is

still a little too flat. Now is the best time for detailed work on the crown.

Picture 9: 2009-11:

The sacrifice branches in the crown must not be allowed to become too thick, otherwise

they will develop ugly scars. That is why they are removed entirely and regrown in the next summer.

The crown is worked on with a pair of pointy sharp scissors. Dead branchlets and branch stumps

are removed. The branches are cut back to one or two buds, and those that grow into the wrong

direction must be removed completely.

Picture 10: 2010-03:

Two years after the restoration, the tree is looking pretty good. Japanese maples are very

handsome trees that in each season look different but always lovely.

This is especially the case in spring. Despite this, the crown must be developed further -

contentment is the end of Art.

Picture 11: 2010-10:

The tree looks very good in the fall too. Yet this is not yet the time to exhibit the tree. The

trunks must continue to be corrected. With strong guy wires they are forced into new

positions. It is advantageous to exaggerate somewhat because the tree will spring back a

little anyway.

Picture 12: 2010-11:

After the guy wires were removed and the crown was carefully cleaned out, the tree was -

for the first time - truly ready for exhibition. Of course, there are still problems.

The large wound on the front trunk is ugly to look at at. But there’s nothing to be

done except to wait for many years. The middle trunk is now clearly the highest and

the crown isn’t entirely flat and even.

Picture 13: 2011-03:

It is tempting to see this lovely new growth as a signal that the tree is ‘finished’ and to

enjoy its beauty from now on. But that would be a compromise over the long term. The

main trunk must continue to grow strongly, the wounds must heal, and the nebari can be

improved much. But something like that doesn’t happen on its own - it requires a lot of

work.

Picture 14: 2011-04:

Here you can clearly see that pinching was completely avoided. The tree was allowed to

grow out fully. Six or more weeks later, the new growth has become fairly long. Now, the

crown is cut quickly with a hedge pruner. In deed, it is like pruning a hedge. The exact cut

is not important, and it even doesn’t matter if leaves are partially cut. Only the long term

success counts.

Picture 15: 2011-10:

During the summer, the tree was cut twice with the hedge pruners. Selected sacrifice

branches were allowed to grow unrestricted. Momentary beauty is sacrificed for long term

quality. It will be a few more years like this. This is the only way to turn an average tree

into a top bonsai.

Picture 16: 2011-10:

In the fall, the tree’s crown is cut again with the hedge pruners, even the sacrifice

branches. As long as there a leaves on the branches it doesn’t make much sense to look

too closely where and what is being cut. That will happen in a few weeks when the tree is

bare. The picture shows real hedge pruners.

Picture 17: 2011-10:

The result doesn’t look too bad at all. But the tree was designed for its winter view. As long

as the leaves are on the tree, you can’t really see it. The crown is nothing but a big ball of

leaves. Amateurs usually prefer that a tree looks good in the summer, but pros prefer the winter

image. A compromise isn’t always helpful and usually leads to weaknesses over all.

Picture 18: 2011-11:

Four weeks later, the leaves are removed. The crown is now carefully pruned. At this point

you can only guess at where the sacrifice branches once grew; the wounds are growing

out well. Two of the trunks in the group must still be forced into a better position.

Unfortunately this is only possible with ugly guy wires.

Picture 19: 2012-04:

This view is reward for all the work. The guy wires are only removed for the pictures, and

then reattached afterward. Because the rest is almost perfect, the big ugly wound in the

front tree is now very apparent. Although it has healed noticeable since the maple was

able to built much energy though it lush growth. The main trunk could also become much

stronger yet - but this is whining at a high level.

Picture 20: 2012-12:

It is November and the leaves are removed again. One can clearly see that some

branches are too long and a few ugly branch stumps were left over. The tree is now

cleaned out with a pair of pointy, sharp scissors. In a few years, one should get the feeling

that Mother Nature is the best artist, and that she creates the best crowns. The hand of

man will eventually become invisible, even though he did so much.

Picture 21: 2012-12:

Slowly the tree is turning out as it should. The crown looks balanced and the entire group

looks as if it had gracefully grown on its own. This, perhaps, gives the viewer the idea that

something like this is result of a hands-off approach. The development so far, however,

teaches the opposite: only through strong and very focused interventions over many years

can such a natural shape be developed.

Picture 22: 2013-02:

The tree was repotted into a very suitable pot by Walter Venne from Germany. The results of the

development thus far are quite presentable. But is is by far not the end of the

development. Much has changed in five growth periods, yet the work continues as before.

In another five years the tree will be better again. The drawback, however, will be that he tree

is not really presentable during much of that time.